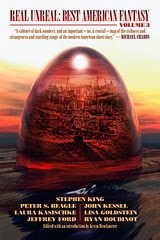

Short Fiction Review #26: Real Unreal: Best American Fantasy Vol. 3

I don’t know whether the third edition of Best American Fantasy, which has found a new home with Underland Press, represents the “best” fantasy, or why it matters whether it’s “American” (meaning, presumably, the United States). Of course, it’s a cliché for any anthology to proclaim its contents represent a “best of,” and the editors who’ve been doing it for a number of years frequently rely on stories from the usual suspects of authors who mostly all publish in the same magazines. While I haven’t read the previous editions of Best American Fantasy, knowing that the series editor is Matthew Cheney and the co-founding editors were Jeff and Ann VanderMeer, I knew what to expect from guest editor Kevin Brockmeier (notwithstanding that Stephen King is the top author listed on the cover page; indeed, his funny riff on the “mysterious telephone call from the dead,” is more in keeping with “traditional” fantasy). This is a collection of _____(New Weird, slipstream, literary, you fill-in-the-blank), the “Real Unreal” about the fantastical state of human consciousness. No elves or adolescents on a quest.

I don’t know whether the third edition of Best American Fantasy, which has found a new home with Underland Press, represents the “best” fantasy, or why it matters whether it’s “American” (meaning, presumably, the United States). Of course, it’s a cliché for any anthology to proclaim its contents represent a “best of,” and the editors who’ve been doing it for a number of years frequently rely on stories from the usual suspects of authors who mostly all publish in the same magazines. While I haven’t read the previous editions of Best American Fantasy, knowing that the series editor is Matthew Cheney and the co-founding editors were Jeff and Ann VanderMeer, I knew what to expect from guest editor Kevin Brockmeier (notwithstanding that Stephen King is the top author listed on the cover page; indeed, his funny riff on the “mysterious telephone call from the dead,” is more in keeping with “traditional” fantasy). This is a collection of _____(New Weird, slipstream, literary, you fill-in-the-blank), the “Real Unreal” about the fantastical state of human consciousness. No elves or adolescents on a quest.

What I didn’t quite expect was the number of authors totally new to me as well as the breadth of source materials, ranging from the tried-and-true (Fantasy and Science Fiction) to the literary (Kenyon Review) to another anthology (Del Rey Book of Science Fiction and Fantasy) to a few I’ve never heard of (The Fairy Tale Review, Pindeldyboz). And the only story I’d previously read was Jeffrey Ford’s “Daltharee,” about the creation of a bottled city and the arrogance and irresponsibility of scientific bureaucracies.

Ramona Ausubel sets the stage with the opening tale of “Safe Passage.” A group of grandmothers find themselves at sea, with no clue as to how they got onboard ship or why. Presumably, they’re dead. Okay, been there before. But the protagonist’s reaction to the banal behavior of her shipmates, and her ultimate decision to take action that results in a sort of enlightened view of her plight, makes the “unreal” here quite “real.”

Similar theological pondering, though much funnier, is Peter Beagle’s “Uncle Chaim and Aunt Rifke and the Angel.” As you’d expect from the title, a blue angel, or at least that is was the creature claims to be, ensconces itself in the studio of the narrator’s uncle, a portrait painter, and in the process becomes the artist’s muse. But angels, and muses, aren’t always what they seem.

Central to any religious/mythological tradition is the question of what happens after you die. Shawn Vestal suggests in “The First Several Hundred years Following My Death” suggests it’s quite boring. At least for people who led boring lives.

In the retold fairy tale department, “The King of the Djinn” by Benjamin Rosenbaum and David Ackert is another of those “be careful what you wish for” parables, particularly if you find comfort in visions of God as merciful. Kellie Wells also bases her story on a familiar tale, that of the Pied Piper, in the”Rabbit Catcher of Kingdom Come”:

When the blood rains began, a week after the children disappeared, Kingdom Comers knew better than to believe what the scientists were saying, which was that the raindrops had merely collided with iron oxide on the way down, consumptive steel mills having coughed the red dust into the atmosphere. Parents, however, were wise to the ways of a carnivorous universe and they knew they were being rained on by their own children…

p. 293

Kuzhali Manickavel’s “Flying and Falling” also concerns a child, one of odd appearance, which makes her father both embarrassed and afraid. The question is whether the growths behind her shoulder blades can really help her fly, or will end up being the death of her.

“For a Ruthless Criticism of Everything Existing,” Martin Cozz writes three paragraphs. I’m not sure that’s enough.

“Cardiology” by Ryan Boudinot posits a town in which the citizenry is tethered to a common heart. Our heroes try to escape their small town lives, but their biological requirements call for infusing desperate measures to make the break. Individual hearts are mended when a collective heart is broken.

While I’m not sure if there’s anything more to the Boudinot story than an absurd premise to the “young lovers escape a stifling home” trope, Will Clarke’s “The Pentecostal Home for Flying Children” takes full aim at religious prejudice and the wishful legends that arise from stupid tragedy. Similarly, Laura Kasiachkle considers whether stupid tragedies of our own making can ever be redeemed in “Search Continues for Elderly Man.”

“The door that Is found at the back of the closet, the morning it was raining and the backyard was mud and she had nowhere to play…” opens Chris Gavalier’s “Is.” Of course, the question is whether Is is delusional, or is she not? Is she? And “is”—the state of being—what we all generally think it is?

One of the centerpieces here is “The Torturer’s Wife” by Thomas Glave. To my taste, it’s a little bit slow taking off, but well worth sticking with. Can there be anything more “unreal” than a person who torture another? Perhaps it is knowing such a person intimately, without really wanting to know?

He who had built for them and the children would soon bring forth that enormous house so far above the city. She who, on His magnificent uniformed arm, lifted high in one easy swing by Him and carried across the threshold, had moved into it with Him and a flock of servants ready for her (surely) imperious command…She who had not, at that time, turner her face to the wall in darkness and pondered the flesh of deadmen. No, nor feared the power of moonlight to bear witness. She, who, at that time, had no fear of skulls or stones raining down upon their (His) roof.

p. 109-110

Another personal favorite is “Pride and Prometheus” by John Kessel. Yes, I know, these Jane Austen pastiches in which either the author or her characters encounter genre inappropriate werewolves or vampires is getting a little out of hand. Kessel at least keeps the genres close, even if the chronology is a bit off. More importantly, Elizabeth Bennet’s meta-fictional meeting with Victor Frankenstein superbly depicts the tragedies and limitations of love and desire. Which was the whole point of the originals that Kessel honors so well.

An equally strange encounter takes place in Rebecca Makkai’s “A Couple of Lovers in a Red Background” in which Johann Sebastian Bach somehow emerges from the narrator’s piano to enliven her love life. But, these mixed-time things don’t, as you might imagine, always work out.

I also very much liked Lisa Goldstein’s “Reader’s Guide.” What starts out as the conventional pedantic attempt to analyze a novel and provoke thoughtful response from a student or book club reader turns into an hilarious meta-fictional fable of another sort invoking Borges and your seventh grade English teacher from hell.

“The Two-Headed Girl” by Paul G. Tremblay is about just that, a girl whose second head of changing personalities may be a substitute for an imagined loving father. Assuming that it is imaginary.

The anthology concludes with “Serials” by Katie Williams, a coming of age tale complete with footnotes. The title refers to the latest popular fad of serial murder, which is all the rage, but could affect the heroine’s final high school grade, not to mention her ex-boyfriend who cruelly dumped her.

Stranger things have happened.