My Fantasia Festival, Day 20: When Animals Dream, Space Station 76, and Welcome to New York

Last Tuesday saw the presentation of the official closing film of the 2014 Fantasia International Film Festival. Film festivals being what they are, there’d actually be another two days of films after that. In any event, I’d manage to see the closer, after catching two other movies earlier in the day.

Last Tuesday saw the presentation of the official closing film of the 2014 Fantasia International Film Festival. Film festivals being what they are, there’d actually be another two days of films after that. In any event, I’d manage to see the closer, after catching two other movies earlier in the day.

I started things at 5:30 with an artful Danish horror film called When Animals Dream. After that, at 7:30, came an American sf comedy called Space Station 76, a send-up of 70s television sci-fi. Finally, at 9:45, came the closing film: Welcome to New York, directed by Abel Ferrara. Once again, I was in for a highly varied evening of cinema.

When Animals Dream was preceded by a short called Sea Devil, co-written and co-directed by D.C. Marcial and Brett Potter. An American fisherman agrees to meet two Cuban refugees at sea and takes them on board; later the ship rescues another man, weirdly mutilated and caked in an undersea growth. The movie goes on to tell a tight (16-minute) story of horror in the deeps. There’s a good atmosphere here, like something out of Jeff VanderMeer or Laird Barron. The short nicely underplays the horror, refusing to specify what’s happening, giving just enough information to be shocking, and deploying sudden cuts to good effect.

When Animals Dream is relatively short itself, at only 84 minutes, but that’s a good length for the film. It’s a simple story, almost a visual tone poem, with minimal dialogue. I thought it worked, but it’s not a film that lives in its plot or even in its characters. Directed by Jonas Alexander Amby and written by Rasmus Birch, it gives us a beautiful introspective atmosphere tha proceeds to slowly unwind a very dark story.

When Animals Dream is relatively short itself, at only 84 minutes, but that’s a good length for the film. It’s a simple story, almost a visual tone poem, with minimal dialogue. I thought it worked, but it’s not a film that lives in its plot or even in its characters. Directed by Jonas Alexander Amby and written by Rasmus Birch, it gives us a beautiful introspective atmosphere tha proceeds to slowly unwind a very dark story.

Marie (Sonia Suhl) is a young (presumably teenaged) girl in a Danish fishing village; as the film opens she’s being examined by a doctor for a strange rash. He finds nothing wrong, and she goes about her life, getting a job processing fish. But there’s something strange going on; she’s changing physically. Meanwhile, Marie has no idea what’s wrong with her unresponsive, wheelchair-bound mother, or why the rest of the village shuns her family. It all soon becomes clear as the film unfolds; Marie has inherited her mother’s condition, which is slowly turning her into a beast.

The Fantasia programmers compared this movie to Let the Right One In, only with werewolves instead of vampires. It’s a reasonable comparison, but these are very different movies. However elliptical Let the Right One In was, it had characters who interacted with each other and grew together. When Animals Dream is in a sense a depiction of Marie’s withdrawal from the world around her. Her interactions with others are minimal, and there’s little in the society around her to encourage her to forge bonds with other human beings. One of the things the film does very well is depict the level of violence and closed-mouthedness of small communities, the way in which individuals are policed and made to conform.

The Fantasia programmers compared this movie to Let the Right One In, only with werewolves instead of vampires. It’s a reasonable comparison, but these are very different movies. However elliptical Let the Right One In was, it had characters who interacted with each other and grew together. When Animals Dream is in a sense a depiction of Marie’s withdrawal from the world around her. Her interactions with others are minimal, and there’s little in the society around her to encourage her to forge bonds with other human beings. One of the things the film does very well is depict the level of violence and closed-mouthedness of small communities, the way in which individuals are policed and made to conform.

I think there’s a good argument to be made that the movie’s specifically looking at the violence directed against women, and the way women are made to conform to societal rules. As I said, Marie begins the movie by being examined by a doctor — being made to remove her clothes, being poked and prodded. As she grows more monstrous, there’s more and more pressure on her to shave her body, even to trim her nails.

So it’s disappointing that at the end she has to be saved from imprisonment by her boyfriend. It does set up a nice conclusion hinting at some kind of society of their own, with an equitable balance of power. But it also seems to some extent to weaken Marie in and of herself. Of course, Marie’s been in virtually every shot of the movie up to that point; she carries the film, and it’s clearly her story. So perhaps giving another character something to do for her has some use.

So it’s disappointing that at the end she has to be saved from imprisonment by her boyfriend. It does set up a nice conclusion hinting at some kind of society of their own, with an equitable balance of power. But it also seems to some extent to weaken Marie in and of herself. Of course, Marie’s been in virtually every shot of the movie up to that point; she carries the film, and it’s clearly her story. So perhaps giving another character something to do for her has some use.

A bigger problem is the way the third act plays out overall; the way the last third or quarter of the movie goes pretty much the way you’d expect. To an extent that’s built into the structure of the movie: Marie’s change isn’t a monthly event but a slow ongoing transformation. She becomes more bestial, and the inevitable explosion isn’t a question of if but of when. The problem is that when it comes it brings no surprises at all.

Still, the movie’s so intensely atmospheric it’s never less than watchable. The doomy soundtrack helps, but there’s also a knack for composition and camerawork here that’s sometimes startling. There’s an image in it of Marie on the rocks by the shore, staring out to sea; as the audience you can place your own interpretation on her, guess at what she’s thinking, but in the end it’s always going to be a matter of speculation. The film as a whole is much like that, with an ending that leaves the future uncertain. But isn’t it often uncertain for teenagers? As thoughtful and unyielding as its main character, I thought When Animals Dream was a real pleasure.

Still, the movie’s so intensely atmospheric it’s never less than watchable. The doomy soundtrack helps, but there’s also a knack for composition and camerawork here that’s sometimes startling. There’s an image in it of Marie on the rocks by the shore, staring out to sea; as the audience you can place your own interpretation on her, guess at what she’s thinking, but in the end it’s always going to be a matter of speculation. The film as a whole is much like that, with an ending that leaves the future uncertain. But isn’t it often uncertain for teenagers? As thoughtful and unyielding as its main character, I thought When Animals Dream was a real pleasure.

I saw that movie in the De Sève Theater, and when it was done rushed across the street to catch Space Station 76 at the Hall. That film’s directed by Jack Plotnick, and co-written by Plotnick with Jennifer Cox, Sam Pancake, Kali Rocha, and Michael Stoyanov, all actors who developed the script through extended improvisation sessions with Plotnick. Plotncik’s talked about “wanting to tell a 70’s suburban story” through the form of filmed 70s science fiction; it’s an interesting idea, and the execution is done with some very inventive craft, specifically in the visual conception of the movie. The drama, however, seemed to me to fail both as science fiction and, more crucially, as a story.

It takes place on what is described as a space station but which flies through space like a vehicle (shades of Space: 1999, I suppose, except the journey’s on purpose, which seems to defeat the “station” part of the phrase “space station”). A new second in command, Jessica Marlowe (Liv Tyler) is coming aboard. She joins a small crew — she’s the 27th person on board — led by a sexually repressed gay captain (Patrick Wilson). She’s drawn to a technician (Matt Bomer), a stoner with a seven-year-old daughter (Kylie Rogers) and a wife, Misty (Marisa Coughlan), cheating on him with his friend Steve (Jerry O’Connell) who in turn is married to Donna (Kali Rocha).

In writing about this movie I have to begin with Seth Reed’s brilliant production design. Everything in the film screams ‘1976,’ from costumes to hairstyles to make-up. The special effects strike a good balance between the crude model-based effects of the mid-70s and the CGI to which we have become accustomed. The technology of the 70s is faithfully recreated, including CRT screens and VCRs and embossing tape.

In writing about this movie I have to begin with Seth Reed’s brilliant production design. Everything in the film screams ‘1976,’ from costumes to hairstyles to make-up. The special effects strike a good balance between the crude model-based effects of the mid-70s and the CGI to which we have become accustomed. The technology of the 70s is faithfully recreated, including CRT screens and VCRs and embossing tape.

It’s actually almost too brilliant. The film sometimes seems too grounded in the 70s, in a way which the 70s sci-fi I remember wasn’t. A wall in the ship’s cafeteria has a wave design in the godawful brown-orange-beige-yellow colour scheme so prevalent in 1970s basements. But the sci-fi TV shows of the 70s weren’t trying to look like somebody’s basement. Far more successful on that count are the hallways, pure white walls with white lighting in recesses. The orchestral soundtrack, composed by Marc and Steffan Fantini, also evokes the time excellently, with evocations of Jerry Goldsmith. Add to that a soundtrack of period songs — mostly by Todd Rundgren — and you have something that sounds like the 70s, as well. On the one hand, the film soon develops a habit of relying on 70s gags to get quick laughs. On the other hand, they’re effective enough gags. Everybody smokes, a nursing mother drinks wine, and what appears to be a man’s hidden stash of pornography is charmingly tame (copies of Poolside magazine with articles about “America’s Top Discos”).

The movie makes a few jokes about the perception of feminism in the 70s; Marlowe’s coming to the station as a professional woman is perceived as a threat by Misty and Donna. But then we find that Marlowe can’t have a baby; she actually is the stereotype of the childless career woman. I found it unclear by the end where the film thought it was going with this thread. There seemed to be an inconsistency in its depiction of Marlowe, who as a result doesn’t seem to develop much through the film.

That’s too bad, because Liv Tyler really shines here. She captures the feel of a 70s leading woman quite well. The cast is generally fine, but I felt had little to work with. The humour is hit and miss, and there’s an aimlessness that soon sets in. When Plotnick and his collaborators decided to parody 70s sci-fi TV, they unfortunately didn’t choose to imitate any sense of story construction. The movie tries to be character-centred, but none of the characters seem credible as human beings, and none develop coherently as a result of their experiences.

That’s too bad, because Liv Tyler really shines here. She captures the feel of a 70s leading woman quite well. The cast is generally fine, but I felt had little to work with. The humour is hit and miss, and there’s an aimlessness that soon sets in. When Plotnick and his collaborators decided to parody 70s sci-fi TV, they unfortunately didn’t choose to imitate any sense of story construction. The movie tries to be character-centred, but none of the characters seem credible as human beings, and none develop coherently as a result of their experiences.

The drama’s unconvincing in a number of ways; we’re expected to believe that in a small space station with only a couple of dozen crew members, two people can have an affair and nobody will know. That seems improbable. Worse: one of the running gags about the captain is how his repression of his sexuality leads him to suicide attempts. But any pathos is undercut when we realise all these ‘attempts’ are foredoomed to failure because of the ship’s automatic security systems. It’s darkly funny once, the first time, when he drops a radio into his bath only for the station to automatically shut down the power. After that we swiftly realise we’re watching a man try to kill himself by methods he knows perfectly well won’t work.

At least by the end of the movie the captain’s plot finds some kind of resolution. It doesn’t intersect with the stories of the rest of the crew, though, which all artificially come to a head at a station Christmas party. Except they don’t come to a head, not really. There’s no conclusion; the film simply ends, with nothing attained, nothing realised, nothing having happened.

At least by the end of the movie the captain’s plot finds some kind of resolution. It doesn’t intersect with the stories of the rest of the crew, though, which all artificially come to a head at a station Christmas party. Except they don’t come to a head, not really. There’s no conclusion; the film simply ends, with nothing attained, nothing realised, nothing having happened.

In the end, there are some funny moments, but the movie doesn’t reach what it’s trying for. It’s an affectless hipster comedy that has a few genuine laughs and a brilliant visual sense of what it’s trying to parody. But while it (admirably) tries to find some depth beyond that, it fails to produce anything compelling. It mainly served to make me interested in giving John Carpenter’s 1974 Dark Star another try at some point in the near future.

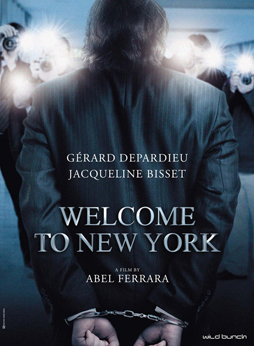

After Space Station 76, I hung around the Hall Theater to watch Welcome to New York. Director Abel Ferrara was present to introduce the film, and stayed to watch it and host a question-and-answer afterward (as it happened, I was sitting about three seats away from Ferrara during the film; it was interesting to hear him burst out laughing at certain points). It’s not a genre film at all, being an only-slightly fictionalised version of the Dominique Strauss-Kahn affair in which Strauss-Kahn, then head of the IMF, was accused of sexual assault and attempted rape of a hotel maid. Gérard Depardieu stars as Devereaux, the head of a powerful international bank who comes to New York, parties with expensive prostitutes, then assaults a maid. He’s arrested, imprisoned, remanded to house arrest while his trial goes on, and finally freed when the charges are dropped — which the film strongly implies happens after Devereaux’s wife, Simone (Jacqueline Bisset), pays someone off.

Towards the end of the film, Simone quotes the old line about the reverse of love being indifference, not hate. Whatever one thinks of the movie, it’s unlikely to leave anyone indifferent. It’s essentially a character piece focussing on the monstrous Devereaux, and his basic sociopathy. The narrative is effectively in two parts: the opening part of the film concentrates on an almost documentary-like recreation of the real events around Strauss-Kahn to the extent they’re knowable, staging photographs and using court transcripts for dialogue. The second part is more introspective, as Deveraux ruminates on his life while under house arrest and clashes with Simone. Depardieu and Bisset are magnificent, conveying the emotional rawness of both characters as well as their intelligence and their history with each other.

Towards the end of the film, Simone quotes the old line about the reverse of love being indifference, not hate. Whatever one thinks of the movie, it’s unlikely to leave anyone indifferent. It’s essentially a character piece focussing on the monstrous Devereaux, and his basic sociopathy. The narrative is effectively in two parts: the opening part of the film concentrates on an almost documentary-like recreation of the real events around Strauss-Kahn to the extent they’re knowable, staging photographs and using court transcripts for dialogue. The second part is more introspective, as Deveraux ruminates on his life while under house arrest and clashes with Simone. Depardieu and Bisset are magnificent, conveying the emotional rawness of both characters as well as their intelligence and their history with each other.

Devereaux is a monster: he has no remorse, and refuses to accept blame for his own actions. There’s a haunting monologue late in the film when he thinks back over his life, and we see one of the most powerful men in the world blaming everyone around him for his situation. The film’s an indictment, not so much of wealth and power, but of the mentality that seems inseparable from wealth and power, the lack of concern for the non-wealthy and non-powerful, the predatory instinct that money enables.

There has been much written about the sexuality in the film. I feel that’s exaggerated; there are three sex scenes by my count, plus the depiction of the assault on the maid. There’s also the beginnings of a sex scene near the start of the film — immediately followed by two of the other three scenes, and then the assault. That seems to have created an impression in some viewers that the whole movie is about sex, which it is not. Depardieu appears completely naked in the film, but in the context of a strip search while he’s in prison; that’s much more to do with showing a powerful man being put in a situation of absolute powerlessness. Some reviewers have spoken of the monstrousness of Depardieu’s nude body in the movie, which I feel also misses the point; Depardieu inhabits the physicality of his character absolutely, down to the smallest grunt or exhalation, and I think he holds himself and presents himself in a way that encourages the audience to perceive him as monstrous — as an emperor who often literally has no clothes, and cannot see himself for what he is.

It’s a powerful film, and I think a success, but I’ll refrain from further discussion here just because there’s no genre element about it at all. Why was it the closing film of the festival? Well, in the long question-and-answer period that followed, Ferrara mentioned that Fantasia was the only (or almost only) festival that would take the film. There is a sense, perhaps, in which the film is like a genre piece in being outside the mainstream; too daring, in a very specific way. Strauss-Kahn has spoken about filing a libel suit against Ferrara, though so far as I can tell no suit has yet been launched. At any rate, it may be that there’s something in the nature of the Fantasia festival that makes it a natural home for an outcast filmmaker. And perhaps that’s allied with its genre orientation; with something unconventional in the festival’s DNA.

It’s a powerful film, and I think a success, but I’ll refrain from further discussion here just because there’s no genre element about it at all. Why was it the closing film of the festival? Well, in the long question-and-answer period that followed, Ferrara mentioned that Fantasia was the only (or almost only) festival that would take the film. There is a sense, perhaps, in which the film is like a genre piece in being outside the mainstream; too daring, in a very specific way. Strauss-Kahn has spoken about filing a libel suit against Ferrara, though so far as I can tell no suit has yet been launched. At any rate, it may be that there’s something in the nature of the Fantasia festival that makes it a natural home for an outcast filmmaker. And perhaps that’s allied with its genre orientation; with something unconventional in the festival’s DNA.

I can’t even begin to summarise here the discussion that followed the screening. Ferrara was incredibly generous with his time, trying valiantly to answer every question from the audience, managing at one point to start a discussion with the crowd about the nature of Devereaux’s venality. The whole thing lasted close to an hour and a half. Ferrara was a charismatic and yet also slightly reticent figure, with his gravelly New York-accented voice, dropping “know what I mean?”s and “you dig?”s liberally through his thoughtful answers.

I will give a few highlights (taken, as ever, from my handwritten notes). The first question was, naturally enough, what about the Strauss-Kahn case fascinated Ferrara enough to make a movie about it? Ferrara chuckled, and said it was a good question that he didn’t want to answer, but would, later, he’d work his way into it. An hour later somebody asked again, and he chuckled again and said he’d get back to it. Which, of course, he never did.

“This shit isn’t like perfect fucking math,” Ferrara said at one point about a choice to use a particular scene. He spoke a lot about finding ways to express what had to be expressed; talking about the line between fiction and documentary, he observed that “you try to find that fine line of, you know, that’s it.” He talked about how once the film was done he was only a member of the audience, unsure whether a final scene between Depardieu and another maid showed that Devereaux hadn’t changed, or whether he had.

“This shit isn’t like perfect fucking math,” Ferrara said at one point about a choice to use a particular scene. He spoke a lot about finding ways to express what had to be expressed; talking about the line between fiction and documentary, he observed that “you try to find that fine line of, you know, that’s it.” He talked about how once the film was done he was only a member of the audience, unsure whether a final scene between Depardieu and another maid showed that Devereaux hadn’t changed, or whether he had.

Ferrara was passionate about allowing Depardieu and his other actors space: “We’re filming him, man, you know what I mean?” and “With Gérard, he is who he is. … You just roll the camera, everybody knows the deal, and that’s what you get. … It’s gonna happen in front of the camera. … They’re all in, these guys.” A bit later: “It’s not like I got a puppet on a string.” He felt his job was “keeping him [Depardieu] in the frame, and keeping a space he can fucking rock n’roll in.”

Ferrara ended the discussion with advice to young filmmakers: “Don’t get discouraged if some festival don’t take your movie. Rent a theatre across the street and show it anyway.” It seemed like an encouraging note to conclude, and so at 1:20 AM I finally ended up heading home. The closing movie was done, but there were still two more films I wanted to see over the next two days.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Space Station 76 sounds like a typical modern comedy – come up with a cute premise/gimmick, don’t worry about actual storytelling, just throw wacky characters and gags out there and then roll the credits around an hour and a half later.

Ah… sorry to read a rather lackluster review of SPACE STATION 76. I rather fell in love with it after reading about it on io9. It sounded brilliant, a film that captured a unique and fleeting period of genre SF.

Well, I think I will still enjoy it, now that you’ve adjusted my expectations accordingly. Assuming I can get it on DVD eventually…